When the now-infamous chain first opened its doors in Seattle on 30 March 1971, its sign bore not a green mermaid but a (more anatomically detailed) brown one, and its mission was purely to sell freshly roasted coffee beansWith more than 21,500 stores in 64 countries and territories, the Starbucks coffee chain has enjoyed the image of omnipresence for so long that jokes about walking across the street from one branch straight into another have themselves become clichéd. In certain cities, it’s simply the reality: Seattle, for instance, where the now universally recognised green mermaid got her humble start.

But when the very first Starbucks opened on 30 March 1971, its sign bore not a green mermaid but a brown one — and a more anatomically detailed one at that. Founders Jerry Baldwin, Zev Siegl and Gordon Bowker (friends from the University of San Francisco, all instructed in the art of roasting by Peet’s Coffee and Tea founder Alfred Peet) drew the theme of their new coffee company from nautical mythology, commissioning that first version of the company’s signature siren and picking a name out of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick – “Starbucks” having narrowly pipped the second-place contender, “Pequod”.

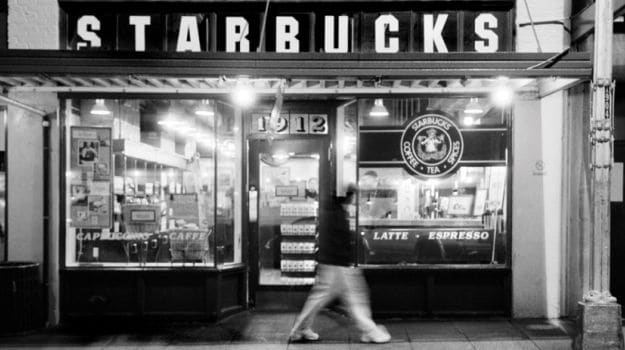

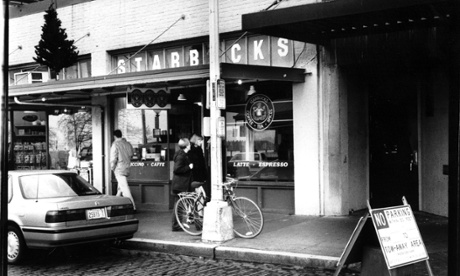

You can still see Starbucks’ original mermaid, baring her breasts and spreading her tails, on the window of the “original Starbucks” (actually the second location of the original Starbucks, to which it moved in 1977) at Seattle’s tourist-beloved Pike Place market. A site of pilgrimage for Starbucks habitués the world over, the store offers not just all the drinks on the company’s modern menu — from normal coffee and espresso to chai tea lattes and caramel Frappuccinos — but a sense of just how much the operation has changed over the decades.

Those who visit the original Starbucks will find themselves at the back of a line stretching well past the small building’s door, and once inside will see nowhere to sit and linger — just as Baldwin, Siegl and Bowker intended. They founded Starbucks not as a place to drink freshly brewed coffee, but as a place to buy freshly roasted beans. The home-brewing coffee aficionados of 1970s Seattle loved it, and demand had grown sufficiently by decade’s end that a curious Howard Schultz – then the general manager of their filter supplier, Hammarplast – paid a visit to No.1912 Pike Place to watch this booming small business in action.

Impressed, Schultz joined Starbucks as director of marketing in 1982 and, on a buying trip to Milan, experienced the cultural awakening that would give the company its destiny – in the form of the Piazza del Duomo’s many coffee bars, all of them serving high-grade espresso, all of them providing quasi-public meeting places for Milanese society. There, amid “the light banter of political debate and the chatter of kids in school uniforms”, the question hit Schultz: why couldn’t American cities have the same thing? And if they could, why couldn’t they serve coffee made with Starbucks-roasted beans?

Unable to convince Starbucks’ founders of the viability of a concept as novel as coffee bars in Seattle, Schultz left the company in 1985. The next year he opened a coffee bar of his own, named “Il Giornale” after one of Milan’s newspapers. Two years after that, he found enough investors to purchase Starbucks outright, which put him in a position, as CEO, to set about his Milanifying mission in earnest: first Seattle, then the United States, then the world.

Starbucks’ greatest period of expansion began in the early 1990s: having already opened money-losing branches in the US-midwest and British Columbia, it then moved profitably into California in 1991, making its initial public offering on the stock market the following year. Starbucks seemed unstoppable throughout that decade and most of the next, opening on average two new stores every day until 2007. But the increasingly globalised company’s fortunes started to mirror those of the global economy, and the following year saw Starbucks shutter hundreds of locations, a grim necessity unthinkable just a decade earlier.

The Great Recession played its part, but Starbucks had also lost its own way, a fact nobody admitted more readily than Schultz himself. Having stepped back from his duties as CEO in 2000, he wrote a memo diagnosing the company’s ills – quickly leaked to the media – which cited “a series of decisions that, in retrospect, have led to the watering-down of the Starbucks experience”. These included the adoption of fast automatic espresso machines bereft of the “romance and theatre” of the old ones, and easily replicable store designs “that no longer have the soul of the past and reflect a chain of stores vs the warm feeling of a neighbourhood store”.

Ostensibly, Schultz had addressed the message to then-CEO Jim Donald — tellingly, a former executive at Wal-Mart, the “big box” retail giant which surely exemplifies the very opposite of what Schultz revelled in on the sidewalks of Milan. As the revisions of Starbucks’ mermaid rendered her bland and asexual, so the revisions of Starbucks itself drained it of whatever local charm could have made its stores into social centres.

Schultz’s Starbucks has always aspired to create what urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg first termed “third places”: real-life sites that “host the regular, voluntary, informal and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work” — exactly, in other words, what the life of the suburb-housed, crime-fearing American commuter lost in the 1970s and 80s. He wrote of the importance of the “‘place on the corner’, real-life alternatives to television, easy escapes from the cabin fever of marriage and family life that do not necessitate getting into an automobile”.

Now that so many street corners seem to have a Starbucks, has the international chain truly become that “place on the corner” where people connect? In fact, Oldenburg dismisses the Starbucks coffee shop as an “imitation”, debilitated by the company’s pursuit of that other quintessentially American obsession, security, and the sterile, predictable environment it produces. “With its overriding concern for safety,” Oldenburg told Bryant Simon, author of Everything But the Coffee: Learning about America from Starbucks, “it can’t achieve the kind of connections I had in mind.”

Walk into a Starbucks today, and you may not notice much connection going on: some customers come in chatty groups, but many others arrive in search of nothing more than a place to open their laptops and get some work done; in effect, using Starbucks not as a third but a second place — their workplace. Most simply grab their coffee and go, never pausing to avail themselves of the chairs and couches provided, while others prefer to keep human interaction to an absolute minimum by using the drive-through window, a resoundingly un-urban feature Starbucks introduced in 1994.

Starbucks’ ongoing retooling and experimentation suggests that Schultz, for all he talks about his company’s resurrection of the “third place”, has yet to hear a sufficient amount of political banter and schoolchildren’s chatter in his stores. Starbucks’ enormous scale and need to service the American demand for frictionless convenience contradicts its mission to replicate the appeal of continental coffee-house culture: how much of a neighbourhood-rooted venue for chance encounter can you provide when you have to run thousands and thousands of them, making sure they all do more-or-less the same thing?

Still, when Starbucks moved beyond its little original store and wove itself into the fabric of American cities, it primed the public for subsequent waves of more genuinely local coffee shops that really do function as third places. These smaller players may accuse Starbucks of abusing its unfair advantage, ignoring city-planning regulations, saturating the market with loss-making stores in prime real estate, and setting its lawyers upon even the faintest hint of trademark infringement, but the fact remains that Starbucks paved the way by introducing an urban coffee culture into places that had never known it before.

Starbucks’ opening in the already coffee-soaked Tokyo in 1996 marked its first step outside North America. The company’s international president, Howard Behar, spoke at the time of losing sleep over stepping into a city with such entrenched competition, but now Japan has well over a thousand Starbucks stores all over the country.

Of the ever-fewer nations in which Starbucks hasn’t yet established itself, one in particular stands out: Italy. Schultz speaks now and again of his intent to bring his coffee bars into the land that gave him the idea in the first place, but also hints that the company doesn’t see that coffee-saturated market as its highest priority.

Milan, for its part, now boasts several branches of Arnold Coffee, a homegrown chain that promises “the American Coffee Experience” – one friendlier to students and laptop jockeys than what traditional Italian coffee bars offer. So closely did Arnold’s founders model its branding on Starbucks’ that they had to alter the original circular logo to avoid a lawsuit – opting instead for an inoffensive and decidedly un-mermaidish coffee mug in profile, which seems like a missed opportunity. If you can get away with a racier logo than the original Starbucks’ anywhere, surely you can do it in Italy.

- Which other buildings in the world tell stories about urban history? Share your own pictures and descriptions with GuardianWitness, on Twitter and Instagram using #hoc50 or let us know suggestions in the comments below