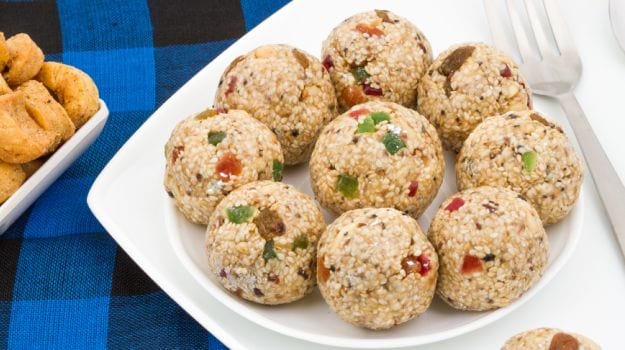

In Lucknow, where I grew up, the arrival of winters was signalled by moongphali wallas doing their daily rounds. We would call out to them, from our sun-soaked gardens, buy 250 gram of freshly roasted, still-warm groundnuts, and make sure that the moongphali peddler put in at least two to three pouches of different kinds of flavoured salt with the groundnuts. The salt was the real reason why we sat out in the sun, shelling the nuts, eating them painstakingly one at a time. We would licking the red rock salt off our fingers, or the peppered and spiced up version that our favourite peddler made himself with God-knows-what. It was a very satisfying snack indeed.Moongphali wallas are now a vanishing lot. In big city retail, you can get neat little packets of roasted peanuts still in their shells from stores but it's not the same. There's nothing like the joy of eating peanut in their freshly-roasted warmth and in the flavoured salts that accompanied them. Nevertheless, this is hardly the only snacking ritual we associate with winters.Most peanut sellers would also bring little rounds of til-patti or gur-patti- sesame and groundnuts set in sugar or jaggery. The rounds were rough, not always brittle enough, home-made by small-time retailers. A more sophisticated version of the same family of snack is of course the gajak, which continues to be a popular signifier of the change in season, when the days get colder and shorter and the body starts to crave more sugar and warming nuts and oils.

Gajak and Chikki

Gajak or gazak, it could be conjectured, gets its name from the generic Arabic word for snack. In northern India, it signifies a class of sweets—usually, a confection made from sesame and jaggery, or sugar. Both sesame and jaggery/sugar are winter ingredients in India and their use in popular snacks and confections shows the seasonal nature of Indian cuisines, whether it be for kings or commoners.

My UP family always favoured the brown gur gajak over the “nouveau” (that's my reading of their tastes) sugar one studded with cashews and almonds. The white sugar gajak, a later day invention, lacks the depth of flavour of the less refined jaggery confection, at least to my mind and palate. But that may only be because of Lucknow food memories.We also pronounced gazak with a “z”, not gajak, as many others did. The “z” connoted cultural sophistication of the Urdu speakers, but also perhaps pointed to the historicity of the gajak, when it may have been concocted as an Indian seasonal snack but on the lines of similar sesame-sugar-nuts confections we see all over the Arab world.Many towns specialise in gajak making, which is quite an art - sesame is broken with hammers, the jaggery or sugar set in layers, and the end result needs to be absolutely brittle and light. But it was Meerut that was designated as the most famous and revered centre for getting this winter treat. If boxes arrived from Ramchandra Sahai, a shop that is more than a century old in that city, it would be considered quite a treat.

Chikki is another similar confection, where nuts like groundnuts (also in season) are set in jaggery or sugar in denser squares than the gajak. The most famous chikki used to be from Lonavala though of course 24X7 retail now means that such specialisations are lost.Daulat ki ChaatOne of the most ethereal sweets however in Lucknow still remains the nimish. You can still savour it only if you visit the city of the Nawabs this season, on the coldest days. Similar to Delhi's Daulat ki Chaat and Mathura's Makhan Malai, which you must eat post a satisfying meal of piping hot kachori-aloo. Nimish is lighter, and comes without the addition of any mawa or khoya that Delhi's streetside makers of Daulat ki Chaat tend to use to thicken the milk.Instead, milk is slowly cooked for hours (the romantic story goes on full moon nights), its froth skimmed off and sprinkled with sugar. This is offered to you on a plate of leaves. The charm of eating nimish at dawn can only be matched by the heartier pleasure of sipping on its cousin, Kadhai ka Doodh, at midnight.Typically, a post dinner drink, Kadhai ka Doodh was made at banquets and by neighbourhood halwais as a warming drink. Milk would be slow cooked, thickened, sweetened and then enriched with slivers of pistachios and almonds. This would be served steaming in fragrant kulhads, unglazed earthen cups.

Street Side Chaats and LadoosStreet snacking in winters cannot be complete without chaat. Fried and crisp. Fried potatoes with lemon and chaat masala are what we associate with the season. However, Aloo ki Tikkiya or Matara, white peas boiled, mashed and then made into crisp patties, defined the winter chaat experience in a gourmet city like Lucknow. Matara was always best served with slivers of ginger, lime squeezed on top; only the less discerning ate it dunked in yoghurt and saunth.Finally, it is also lentils, considered a warming food according to Ayurveda, that come into their own as a pop ingredient this time of the year. You only have to see the prevalence of Ram Ladoos—fritters made from moong dal, served on a bed of grated radish – in Delhi, and of sautéed moong dal, sprinkled with chaat masala, onions and chillies, in the bazaars of UP to understand that.Winters means that cooked dal stays for longer, without getting fermented in the heat. It is easier to turn it into snacks that will be sold on the streets with the most basic of cooking facilities. Dal Chilas and Dal Halwas also start making an appearance at popular halwai stalls this time of the year. Filling and warming - enough to let the cold roll away.

About the Author:Anoothi Vishal is a columnist and writes on food for The Economic Times and NDTV Food, and runs the blog amoveablefeast.in. She tracks the business of restaurants and cuisine trends and also researches and writes on food history and the cultural links between cuisines. Anoothi's work with community-based cuisines led her to set up The Great Delhi Pop-Up three years ago, under which she promotes heritage, regional and community-based cuisines as well as researched and non-restaurantised food concepts. She has also been instrumental in reviving her own community's Kayastha cuisine, a blend of Indo-Islamic traditions, which she cooks with her family and has taken across India to a diverse audience.Disclaimer:The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. NDTV is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information on this article. All information is provided on an as-is basis. The information, facts or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NDTV and NDTV does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.