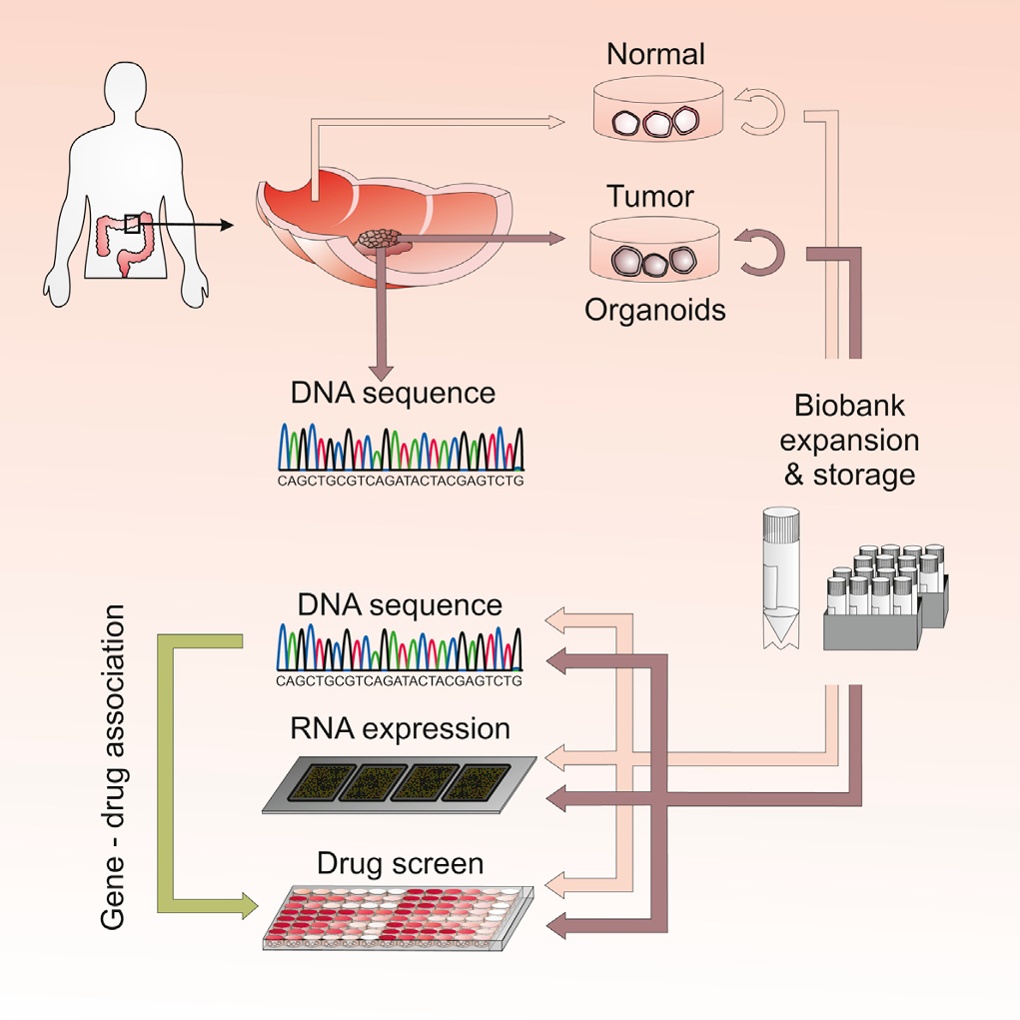

Scientists have created the world’s first “living biobank” of patients’ tumours and used the tissue to identify the most promising drugs for each person’s disease.

Tiny biopsies of the patients’ tumours were grown into clumps of cells and kept alive in the lab, so researchers could study their specific mutations and subject the tumours to more than 80 anti-cancer drugs.

Geneticists at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge said the work marked a step towards more personalised medical treatments that target cancer tumour by tumour in individual patients.

The researchers grew what they call 3D organoids from both cancerous and healthy tissue biopsies taken from 20 patients with bowel cancer. All of the patients had received surgery to remove their tumours and were not having further treatment.

Tests on the organoids showed that they closely mimicked the patients’ tumours in many ways, including their genetic profiles, the variety of cells they contained, and the structures they formed.

“The beautiful thing here is that we’ve shown we can grow these organoids in the lab and they look a lot like the tissue from which they were taken, so they should be much better models for studying cancer,” said Mathew Garnett, a researcher at the Sanger Institute.

“This opens up amazing opportunities to ask questions about the biology of the patients’ tumours, the genetics of their tumours, and to see how that patient might respond to different cancer drugs,” he added.

About 41,000 people in the UK are diagnosed with bowel cancer each year. Doctors use a combination of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation to treat patients, but anti-cancer drugs work better in some patients than others.

“Cancer is a very diverse disease and we often find that some patients respond to a drug while others don’t. The reasons are often poorly understood, but we can use the organoids to try and understand that better,” said Garnett whose study is published in the journal, Cell.

“Ultimately this living biobank should enable us to identify populations of patients that we can predict will be most likely to benefit from a specific drug,” he added.

From the 20 patients, the scientists grew 22 tumour organoids and 19 healthy tissue organoids. Each one took from two to six weeks to grow. By comparing the genetic make-up of the diseased and healthy organoids from each patient, the reseachers identified specific DNA mutations that seemed to be driving each of the patients’ tumours.

They then broke the organoids up and exposed the tumour tissue to 83 approved or experimental anti-cancer drugs. The drugs had varying effects on the cancers, with some having little impact because of known mutations that made the tumours resistant.

But the drug screening also raised hope for some patients. One tumour that carried a mutated RNF43 gene was swiftly destroyed by a drug that blocked a protein called porcupine. Researchers now hope to build up a library of living tumours to help them find drugs for a broader range of cancers.

The results from the drug tests were not used to influence the patients’ care because they had already been treated, but the work demonstrated how the procedure might help other patients in the future.

“An aspiration that is three to five years away is to take someone’s tumour, grow it in the lab, test what drugs it responds to, and then use that information to decide the patient’s treatment. There are still some technical hurdles, but we are not miles away from that,” said Garnett.

Marc van de Wetering, a senior researcher at the Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands and first author on the study, said the team was now exploring whether organoids predicted how well patients responded to cancer treatment. To test this, researchers are making organoids from cancer that has spread in patients. Any drugs the patients receive are given to the organoids too, to see if they mimic the effects seen in the body. If they do, then in the future organoids could be used to steer patients’ treatment. The study of a few hundred patients is expected to run for a few years before the results are clear.

Tim Maughan, professor of clinical oncology at Oxford University, said the study highlighted new opportunities for treating patients with certain genetic changes with drugs that had not been previously considered in bowel cancer.

“This sort of information is of great potential use in designing personalised medicine trials. One such trial is currently running in many hospitals across the UK, called FOCUS4, which is linking the genetic tests on a patient’s tumour to potential drug sensitivity in bowel cancer. This study provides new insights which could help select new drug treatments for patients based on aspects of the molecular make up of their own cancer,” he said.The Sanger Institute team hope that the use of organoids will eventually help identify effective personalised treatments for patients. Video: Sanger Institute Image via Thinkstock