Starting with mayo and cookies, the ex-linebacker’s Hampton Creek company is using science to change the food industry – and has attracted big-name investors

From the street, Josh Tetrick’s office in San Francisco’s up-and-coming industrial South of Market district looks like a coffee shop with half a dozen young hipster-types drinking coffees while tapping away on MacBook Airs on a long wooden bench as a golden retriever, yorkshire terrier and poodle cross lounge at their feet.

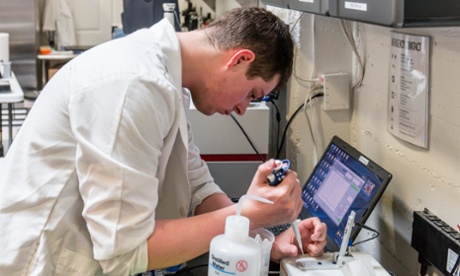

Once inside, the office turns out to be part-coffee shop, part-science lab. At the back, a team of scientists in lab coats are busy with titration kits and molecular formulas, while Michelin-starred chefs are cooking up some scrambled eggs – without cracking any eggs.

Welcome to the headquarters of Hampton Creek: Tetrick’s three-year-old startup which he hopes will disrupt the world food industry by replacing eggs (and other water-intensive foods) with plants.

“Although what we’re doing may sound odd to outsiders, the neighbours were glad when we moved in,” says Tetrick, a strapping 34-year-old former football linebacker from the deep south. “This used to be a Hell’s Angels hangout and it was listed on Google Maps as having orgies.”

Now Tetrick is using the nondescript building by the corner of Sheridan and 10th Street as mission control to take on the world’s biggest food companies and help save the planet.

Tetrick says the motivation for starting Hampton Creek, which was born in his Los Angeles apartment in December 2011, was twofold. First, his noticing that the global food industry was “fucking up the world” and, second, as a way to encourage people who didn’t really care what they were eating to eat slightly more healthily. Tetrick’s father was the original inspiration. “My dad didn’t give a fuck what he was eating. It was all shitty, shitty food and I realised there were people eating like that all over the world,” he says.

Tetrick, who is from Alabama and read law at the University of Michigan Law School, came up with an idea. He admits it wasn’t much of a business plan; it contained just 14 slides and didn’t explain exactly how he planned to tackle the problems of the global food industry.

Even so, it got him a $500,000 investment from Vinod Khosla, the billionaire venture capitalist and founder of Sun Microsystems.

“It was a bet,” says Tetrick. “He was betting on an idea. When you start explaining the [global food] system, people say ‘you’ve got to be fucking kidding me’.”

Tetrick has since convinced some of the world’s most prominent investors to take a punt on him. Shareholders include Asia’s richest man Li Ka-shing, PayPal founder Peter Thiel, former Yahoo boss Jerry Yang and Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin. It has also been backed by Bill Gates as a company shaping the future of food.

Tetrick has refused to take investment from other big names. “We’ve turned a lot of folks down because they either don’t think long-term enough or they would be too hands-on; we don’t want hands-on …

“I mean you’re investing in Hampton Creek – you’re investing in fucking moonshot. You’re not investing in Hampton Creek because you’re going to make a little money. You’re either going to make nothing or you’re going to make a shit tonne.”

Tetrick says he’s more concerned about changing the world than making money. “We’re beginning to have an impact with water not being used, with land not being used, with carbon emissions not being pushed into the atmosphere, with to some extent chicken eggs not being used as much,” he says. “That’s what we will continue powering away for.”

At present, Hampton Creek’s two main products are egg-free mayo and egg-free cookies (which the company bills as cookies that “can change the world”). Instead of eggs, Hampton Creek’s Just Mayo is made from Canadian yellow pea, a type of split pea.

At first, Tetrick says, the company had no idea which plants could be used as substitutes for the proteins found in eggs, so they just tried a bunch of different ones. The key characteristic is high protein surface hydrophobicity, which allows emulsification.

To make the mayo, the Canadian yellow peas are ground down into a powder and added to oil and other ingredients found in mayonnaise in place of egg. He says there’s “a certain rhythm to how we mix it”, but that’s about it.

The mayo is on sale at Dollar Tree, Whole Foods and Costco (the latter two also sell the company’s cookie dough) in the US and will go on sale at Tesco in the UK soon. Global catering company Compass Group, which supplies 4bn meals a year to school canteens, hospitals and prisons across the US and UK, has recently replaced all its mayonnaise and cookies with Hampton Creek products. According to the company’s own calculations, for every dozen cookies eaten 294 quarts (278 litres) of water are saved.

Tetrick, who has no scientific training, is pained by the suggestion that what his company is doing is unnatural and the “Frankensteinisation of food”. “These guys [his scientists] don’t synthesise things, they’re not splicing DNA together, they’re not growing anything in a petri dish.”

Hampton Creek, which was named after his former roommate’s deceased dog, has made some enemies – mostly among global food conglomerates.

Unilever, the Anglo-Dutch giant that owns Hellmann’s, filed a lawsuit last year arguing that Hampton Creek shouldn’t be allowed to market its product as “mayo” because it doesn’t contain eggs, which mayonnaise must legally contain in the US.

Tetrick said Hampton Creek’s case was threefold. His product is called Just Mayo, not mayonnaise, and it was clearly labelled as egg-free. “The third thing was a little more controversial, but it’s how we felt,” he says. “It was like ‘fucking come on guys’. Guys, you have done more than most companies to embed sustainability in your food chain. Your CEO Paul Polman has talked about transformative business models to make the world a better place. Come on, aren’t there better things you can do with your time and your money. It’s not exactly a legal analysis but that third element is what convinced Unilever to drop the case.”

After 34 days, Unilever withdrew its lawsuit. Tetrick says Unilever’s lawsuit was a huge public relations win for Hampton Creek. “It gave us an opportunity to talk about what we are doing and why, and it got global recognition,” he says. “After the lawsuit people thought ‘there’s something about this brand, there’s fight in it’. [People thought] this is a brand that is OK with pissing people off.

“Everyone doesn’t have to like what we’re doing. In fact, if everyone likes what we’re doing we’re probably screwing up more than we otherwise would be.”

Next on Tetrick’s agenda is scrambled eggs. His head chef, Ben Roche, previously executive pastry chef at Chicago’s Michelin-starred Moto restaurant, is experimenting with various (top secret) plants to try to find one that will provide the same texture as scrambled egg.

A sample the Guardian tasted was better than some hotel breakfast scrambled eggs.

Tetrick plans to expand to 30 products within three years ranging from custard to pasta. “If mayo is more than 3% of our revenues in three years, like, we’re doing something wrong.”

After that, he is planning on creating a cheap easily produced high-protein snack that could be used to help eliminate hunger in Africa. “Why does food not serve you, why does food not serve this country, why does food not serve the world? I mean what is the problem?

“What if there is a protein snack for the developing world, what if there’s an interesting highly nutritious protein snack that potentially we could distribute through the World Food Programme?

“Two and a half billion live in energy poverty without refrigerators. I don’t even know what it means necessarily. [But] I do know that you’re a dumb company if you’re not thinking about serving them.

“Part of the meaningful impact we’ll have is if people can see there’s a shit tonne of money to be made riling people up and solving problems, whether that’s a giant food company or some 12-year-old girl somewhere going ‘fuck this, fuck school, I want to do something else’.”

In December, Hampton Creek secured a further $95m of investment, which Tetrick says values the company “in the neighbourhoods of half a billion”.

He refuses to say exactly how much of the company he still owns but confirmed he still holds “quite a bit”. “We’ve been valued as a company that really has the potential to do something. With that valuation I have been able to retain a bit more ownership.”

That means that Tetrick, raised in a working-class family in Birmingham, Alabama, is on paper at least a very rich man. “Yeah, but I don’t really … I literally do not give a fuck about money at all,” he says. “I don’t know if this makes my investors feel good or not, [but] I have a golden retriever, I have a company car, I have an apartment in [San Francisco’s fancyish] Potrero Hills.”

Tetrick says he wouldn’t sell out even if he was offered $1bn. “I just want to get at this,” he says. “Someone could write a cheque right now for $2bn for Hampton Creek. The idea of accepting that … I would feel nothing but sadness.

“I was struggling in my life finding what I actually wanted to do. I had a dream of being a professional athlete, [but] I wasn’t good enough. I spent a while trying to find my way in Africa.

“I have finally found what I want to do, what I am good at. I don’t go to sleep at night thinking that I am bullshitting myself, and that feels good.”

Josh Tetrick in his coffee-shop-style Hampton Creek office in San Francisco: ‘We’re beginning to have an impact,’ he says. Photograph: Christopher Stark for the Guardian