Born in 1876, Helen's girlhood unfolded alongside her father's research in nutrition and agriculture. While the primary family home was in Middletown, Connecticut, the Atwaters spent time abroad in Germany and France, as Atwater conducted research and learned new techniques developed by European scientists. Such colleagues often visited the Atwater home. One can imagine a young Helen curiously listening in on Atwater's conversations about the energy value of food, economic consumption,and good health. She grew up as Atwater headed the Office of Experiment Stations at Wesleyan University. There he conducted experiments with the calorimeter, identifying the number of calories within foods, as well as the specific number provided by each macronutrient: carbohydrates, proteins and fats.

Despite her interest in nutrition, Helen did not pursue its study in college, as it was a rarity for women to attend university in the late 19th century, let alone major in the sciences. One of the most esteemed leaders of the domestic science movement, Ellen Richards, was the first woman ever admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She gained entrance in 1870 as a "special student," a status that demarcated and demoted her within the classroom for her sex. In fact, when Helen pursued higher education in the 1890s, only 2.2% of U.S. women aged 18 to 21 years attended college. Perhaps for such reasons, Helen pursued a degree not in science, but in modern languages at Smith College, an institution of note to foodies; Julia Child would graduate from Smith with a degree in history in 1934. Helen, on the other hand, progressed through her studies quickly, graduating in three years in 1897.

At a time when few women were engaged in scientific research, Helen began work after graduation as an editorial and research assistant with her father in his laboratory. She supported his research efforts, while also gaining experience and a professional network, which bolstered her own career aspirations. Combining her editorial skills and her growing nutrition knowledge, Helen assisted her father in preparing the first popular presentation of his research: "Principles of Nutrition and the Nutritive Value of Food," published in 1902 in Farmers' Bulletin No. 142. On her own, she also published "Bread: The Principles of Bread Making" in 1900 and "Poultry As Food" in 1903.

After Wilbur Atwater suffered a career-ending stroke in 1904, Helen not only cared for him with her mother, but also served as a conduit to his research. During this time, Helen recounted to a relative "the agonizing days when for three years she sat outside her father's bedroom door making up stories about his experiments at the laboratory to assure him all was going well." Atwater died in 1907. Helen was 28 years old.

Going forward on her own

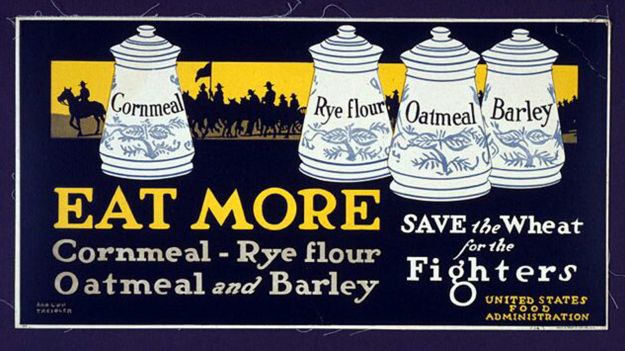

After her father's death, Helen took charge of his papers and later joined the United States Department of Agriculture's Office of Home Economics as a writer and editor, where she worked until 1923. Employing her writing abilities, editing skills, and knowledge in nutrition and home economics, she contributed to a variety of projects during her tenure. She developed materials for both nutrition professionals and the lay public. For example, in 1915 she published "Honey and Its Uses in the Home" (1915) with Caroline Hunt, which discussed honey's chemical composition, nutritive value and economic cost. It also recounted extensive experiments on the relationship between honey, sugar, and sweetness and includes dozens of recipes. In 1917, she and Hunt co-published "How to Select Foods," one of the first official American food guides, which guided early federal nutrition policy. Helen also worked on myriad food conservation efforts during World War I, including "meatless Mondays" and "wheatless Wednesdays."

Beyond her contributions within the USDA, Helen also served as the first full-time editor of the Journal of Home Economics. Pint-sized at just taller than 5 feet, Helen brought experience, energy and good humor to her work on the journal and within the American Home Economics Assn., where she worked for 18 years, from 1923 to 1941. She published, edited and oversaw countless newsletters, articles, pamphlets and guides, continually seeking to inform the public on nutrition science and how it could influence everyday life. She also promoted home economics as an educational and career path for women, sharing her experiences and offering advice. She served on multiple government and organizational boards and groups in the U.S. and abroad before she retired. She died in 1947 at the age of 71.

Dr. Melissa Wilmarth has researched the life and achievements of Helen Atwater, concluding: "She was an editor extraordinaire, a leader of leaders, and a model for the 21st century."

March is Women's History Month and National Nutrition Month, an apt time to reflect on Helen Atwater's contributions to women's experiences in higher education, scientific research, and government work - perhaps while also trying her honey cake.

Yellow Honey Cake

This recipe is reproduced as it appeared in "Honey and Its Uses in the Home," published in 1915 by Helen Atwater and Caroline Hunt in the United States Department of Agriculture Farmers' Bulletin.

Ingredients

1 1/2 cups flour

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1/8 teaspoon cloves

1/2 cup sugar

2 egg yolks

2/3 cup honey

Directions

1. Sift together the flour and the spices.

2. Mix the sugar and egg yolks, add the honey and then the flour gradually.

3. Roll out thin, moisten the surface with egg white, and mark into small squares.

4. Bake in a moderate oven (about 350 F).

Copyright Emily Contois via Zester Daily and Reuters Media Express