Far-reaching food industry rules aimed at reducing food-borne illness in the United States have become final, the federal government announced, nearly five years after Congress passed a law requiring an overhaul of the nation’s food-safety system.About 48 million Americans a year become sick from food-borne diseases and 3,000 die, according to federal data, tallies that many health officials say could be significantly reduced if the food industry took a more proactive role in monitoring and reducing risks. But carrying out the law, the Food Safety Modernization Act, which was the first significant update of the Food and Drug Administration’s food safety authority in 70 years, has been criticized as slow.Two of the final rules that will underpin the law — detailing exactly how companies need to change their practices to comply — were made public Thursday, including a requirement that food processing companies actively take steps to reduce risks, instead of acting only after someone gets sick. They will start to take effect next summer.

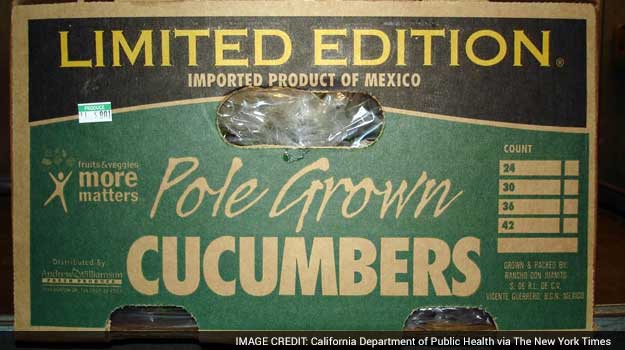

“It’s a big step forward,” said Sandra Eskin, director of food safety at the Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington.Consumer advocates say the need is urgent. Just this week, federal health authorities said an outbreak of salmonella, most likely caused by cucumbers imported from Mexico, had sickened 341 people in 30 states. Seventy of those people were hospitalized and two have died, one in Texas and one in California. Also this year, Blue Bell Creameries, an ice cream producer with plants in Texas, Oklahoma and Alabama, had to recall all its products after 10 people became ill with listeria from eating them. Three of those people died.The new rules are related to the processing of foods like peanut butter and ice cream. A separate rule on fresh produce is not expected to become final until later this year. Today, nearly half of fresh fruits and one-fifth of vegetables in the United States are imported, a relatively recent shift that has created new difficulties for monitoring food safety.The new rules require food manufacturers to put in place written food safety plans that detail points in the manufacturing process that could be risky and steps they are taking to minimize that risk.Michael R. Taylor, deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the FDA, said the law’s mandate was to “transform the whole food safety system,” a task that was sweeping and required months of negotiations with a vast array of groups like state and foreign governments, farms, food manufacturers and food importers. That the first rules became final in less than five years was a significant accomplishment, he said.He said that some large food producers already had sophisticated systems in place, for example, regular swabs of floors, drains and walls inside facilities to check for contaminants, and that the new rules had to be flexible to allow for pre-existing safety systems that were working.“We don’t want to issue regulations that force change for change’s sake if they don’t make a real difference in food safety,” he said. “Getting high rates of compliance is really the crucial issue.”The rules allow for some exemptions, including ones for small producers with less than $1 million in sales, something that some consumer advocates said amounted to a bit of a loophole. But for the most part, the consensus among advocates was that the rules were a vast improvement.The food industry also seemed satisfied. In a statement, the Grocery Manufacturers Association, a trade group representing food and beverage producers, praised the FDA “for the deliberative and inclusive approach it took in developing these regulations.”Under the rules, food makers will be required to keep written records, effectively a sort of safety activity log for the production center, and FDA inspectors will have the right to review them. That is a big change. Before, plants were not required to hand over records to inspectors, said David Plunkett, a senior staff lawyer at the Center for Science in the Public Interest’s food safety program. In 2007, an operator at a Peter Pan peanut butter factory refused to hand over records to an FDA inspector, and some months later, around 600 people fell ill from its products, he said.“It was like telling the police you can go where the robbery is happening but you don’t have the right to search for the robber,” Plunkett said. “Now they have access to a lot of information so they know what the plants are doing, even on days when they are not physically at the plant.”The FDA will have far greater enforcement powers, too. Before the law, FDA officials inspected plants only about once every 10 years, Eskin said. The law bumped that up to at least once every five years for high-risk plants and, starting early next year, to once every three years. The FDA will also have the authority to close a facility when plans are inadequate. Previously, the agency had to wait until people became sick.In a phone call with reporters, Taylor reiterated concerns that carrying out the new duties would be difficult without significantly increased financing. The Obama administration has asked for $109.5 million in additional funding for fiscal 2016, but the House and Senate funding bills would provide less than half that.© 2015 New York Times News Service

“It’s a big step forward,” said Sandra Eskin, director of food safety at the Pew Charitable Trusts in Washington.Consumer advocates say the need is urgent. Just this week, federal health authorities said an outbreak of salmonella, most likely caused by cucumbers imported from Mexico, had sickened 341 people in 30 states. Seventy of those people were hospitalized and two have died, one in Texas and one in California. Also this year, Blue Bell Creameries, an ice cream producer with plants in Texas, Oklahoma and Alabama, had to recall all its products after 10 people became ill with listeria from eating them. Three of those people died.The new rules are related to the processing of foods like peanut butter and ice cream. A separate rule on fresh produce is not expected to become final until later this year. Today, nearly half of fresh fruits and one-fifth of vegetables in the United States are imported, a relatively recent shift that has created new difficulties for monitoring food safety.The new rules require food manufacturers to put in place written food safety plans that detail points in the manufacturing process that could be risky and steps they are taking to minimize that risk.Michael R. Taylor, deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the FDA, said the law’s mandate was to “transform the whole food safety system,” a task that was sweeping and required months of negotiations with a vast array of groups like state and foreign governments, farms, food manufacturers and food importers. That the first rules became final in less than five years was a significant accomplishment, he said.He said that some large food producers already had sophisticated systems in place, for example, regular swabs of floors, drains and walls inside facilities to check for contaminants, and that the new rules had to be flexible to allow for pre-existing safety systems that were working.“We don’t want to issue regulations that force change for change’s sake if they don’t make a real difference in food safety,” he said. “Getting high rates of compliance is really the crucial issue.”The rules allow for some exemptions, including ones for small producers with less than $1 million in sales, something that some consumer advocates said amounted to a bit of a loophole. But for the most part, the consensus among advocates was that the rules were a vast improvement.The food industry also seemed satisfied. In a statement, the Grocery Manufacturers Association, a trade group representing food and beverage producers, praised the FDA “for the deliberative and inclusive approach it took in developing these regulations.”Under the rules, food makers will be required to keep written records, effectively a sort of safety activity log for the production center, and FDA inspectors will have the right to review them. That is a big change. Before, plants were not required to hand over records to inspectors, said David Plunkett, a senior staff lawyer at the Center for Science in the Public Interest’s food safety program. In 2007, an operator at a Peter Pan peanut butter factory refused to hand over records to an FDA inspector, and some months later, around 600 people fell ill from its products, he said.“It was like telling the police you can go where the robbery is happening but you don’t have the right to search for the robber,” Plunkett said. “Now they have access to a lot of information so they know what the plants are doing, even on days when they are not physically at the plant.”The FDA will have far greater enforcement powers, too. Before the law, FDA officials inspected plants only about once every 10 years, Eskin said. The law bumped that up to at least once every five years for high-risk plants and, starting early next year, to once every three years. The FDA will also have the authority to close a facility when plans are inadequate. Previously, the agency had to wait until people became sick.In a phone call with reporters, Taylor reiterated concerns that carrying out the new duties would be difficult without significantly increased financing. The Obama administration has asked for $109.5 million in additional funding for fiscal 2016, but the House and Senate funding bills would provide less than half that.© 2015 New York Times News Service

Advertisement