No grain no pain? Last year UK sales of gluten-free products reached 184m pounds - up 15% from 2013. Photograph: Alamy

Up to a third of American adults are now avoiding gluten, and numbers in Britain are growing rapidly: gluten-free sales are soaring. But is it really our dietary enemy - or, as Jennifer Lawrence thinks, just the 'new cool eating disorder'?

If your nearest supermarket is anything like mine, you will have noticed increasing space being given over to "free from" products. Sporting images of foods that look as good as their regular counterparts, the packaging hints at health benefits; the labels proclaim their contents free from lactose, dairy, and most commonly, gluten. Gluten-free bread, cakes, curry sauces and pesto; displays of gluten-free easter eggs. Such is the hype that foods that have never traditionally contained gluten are now marketed by some producers as "naturally gluten-free". As well as a dedicated aisle, around the store you will find gluten-free ready meals in the "healthier choices" chiller cabinet, and gluten-free chicken nuggets in the frozen food aisle.

There was a time, not that long ago, when gluten-free food was only available on prescription - it was a medical need for a small minority of people. Humans, after all, had been consuming gluten in some form for thousands of years. But this was the era that we may come to know as BG (Before Gwyneth). For many, gluten is now the enemy. As one US talkshow host joked last year, in Los Angeles it is "comparable to satanism".

Over the last few years, the market in gluten-free products has exploded. Alarmist, bestselling diet books have linked gluten to autism, depression, Alzheimer's, multiple sclerosis and diabetes, among others. In 2013, Gwyneth Paltrow revealed she had put her family on a gluten-free diet, "curing" her son's eczema. The actor Jennifer Lawrence has called it the "new cool eating disorder". A piece in the New York Times noted last year: "Eating gluten-free is dismissed outright as a trend for the rich, the white and the political left." All of which must be quite an irritant for those who suffer an adverse reaction to consuming gluten, and are seeing their dietary needs dismissed as a trend.

The backlash is particularly prominent in America, where the diet has really taken hold (about a third of American adults are trying to cut gluten out, according to a Consumer Reports National Research Center survey). In October, an episode of South Park saw the whole town go gluten-free (the stuff, it was discovered, made one's penis fly off). And on the Jimmy Kimmel show in the US - he of the "satanism" quip - several self-diagnosed gluten avoiders were asked what gluten actually was. None of them knew. It was something to do with bread, they said, or pasta. Either way, it was bad for them.

Gluten is made up of two protein groups, gliadin and glutenin, brought together when flour and water are mixed to make a dough for bread and other processed foods, giving structure and elasticity. It is found in wheat, but also in other grains such as barley and rye. It isn't simply enough to avoid bread, pasta and cakes - gluten can be found in sauces, stock cubes, sweets and a wide range of other products. It is vital for people with coeliac disease to avoid it - their immune system reacts to gluten, damaging the lining of the small intestine which hampers the absorption of nutrients, and can cause anaemia, weight loss, fatigue, bloating and pain. The long-term consequences of going undiagnosed and continuing to eat gluten include osteoporosis, anaemia and even bowel cancer. Around 1% of the population is thought to suffer from coeliac disease - and of those, nearly three-quarters remain undiagnosed - accounting for the small proportion of people who actually need to buy gluten-free products. But millions of others are.

For all the mockery, it looks as if the diet is here to stay. Last year in the UK, sales of gluten-free products reached 184m pounds, up 15% from 2013. A report by Mintel found 15% of households were avoiding gluten and wheat - more than half because they believed it was part of a healthy diet. One in 10 new food products launched in 2014 were gluten-free; nearly double what it was two years ago. "That gives you an idea of the rate of growth," says Douglas Faughnan, senior food and drink analyst at Mintel. Increasing numbers of the general public are buying gluten-free products, he says, because "they believe it to be healthier".

In the US nearly a quarter of all product launches have gluten-free claims; in Britain, there is still room for growth. "There are a lot of categories where there is quite a low level of gluten-free innovation, if you look at things like beer," says Faughnan. "Pizza is another area which has only developed over the last year." The price is prohibitive - it can cost three or four times that of a regular product - but is likely to come down as big food makes inroads into the gluten-free market (Nestle launched gluten-free cornflakes last summer). And it's not just about what's on the supermarket shelves. There are ever more gluten-free dishes in restaurants - and new EU food labelling rules mean gluten, along with potential allergens, must now be listed on menus, as well as packaged foods. There are entirely gluten-free restaurants. You can go on gluten-free holidays.

If it is a fad, it comes as both a blessing and a curse for people with coeliac disease. One sufferer told me her "pet hate" was the number of people who "empathise" with her, claiming they can't eat bread either, then happily devour a bowl of pasta, or give up wheat for six months before miraculously going back to it with no ill effects. She, meanwhile, has a lifelong condition. Another coeliac, Katherine Busby, 35, from York, was diagnosed 12 years ago. Back then, she would get gluten-free food on prescription - a monthly loaf, pasta, crackers and a "treat". For the first year, following a gluten-free diet was quite difficult. "I'd find something I could eat and stick to it - I'd eat a lot of jacket potatoes."

She remembers going on holiday with her mother, who packed her handbag with miniature cheeses in case there was nothing she could have; the awkwardness of explaining to people who had never heard of the condition what she could and couldn't eat. When more people started cutting gluten out and there were magazine articles about it, Busby says, "I'd get comments like, 'that's really fashionable' or 'how much weight are you trying to lose?' That's frustrating because I don't like to be thought of as fussy. But on the other side, I haven't had [food on] prescription now for about seven years because you can get food everywhere. I can go to pretty much any restaurant without calling beforehand ... Having a bigger number of people following it means the companies making the food can invest more in making it nice." In the last three or four years gluten-free food has improved substantially, she says.

There has been a worry, says Sarah Sleet, chief executive of Coeliac UK, that people who choose to go gluten-free "could easily choose not to do it, and then the industry could shrink and where would that leave people with coeliac disease? But there's no sign of it. This trend has been really solid, we just keep seeing more and more growth, and it's a worldwide phenomenon. What I'm hoping is that just as 'vegetarian' has become just another normal option, this will embed itself and there just will be gluten-free options."

The number of people with coeliac disease, or symptoms they claim are related to eating gluten "is undeniably something I have watched rise year on year for the last two decades," says Professor David Sanders, consultant gastroenterologist and co-founder of the Sheffield Institute of Gluten-Related Disorders. Coeliac disease has diagnostic tests, but something that has come to be known as non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is less clear-cut: people who test negative for coeliac disease report symptoms such as joint pain, headaches and gastrointestinal problems they believe are related to eating gluten, even though there is no consensus on how to diagnose it, or even whether it exists.

"I've been in this field for almost 20 years and when we ran the first screening study for coeliac disease in the mid-1990s, everybody said it was a very uncommon disease," says Sanders. "They were surprised to find 1% of the population was affected." He mentions that, he says, because he thinks the understanding of NCGS is now at that point, where people are sceptical it is a genuine condition, or exists in relatively large numbers. "We looked at more than 1,000 healthy volunteers and 13% of them said they had symptoms when they ate gluten and of that group, 2.9% were actually on a gluten-free diet. The reason they were doing that was they had noticed symptoms which had improved on the withdrawal of gluten."

Others have suggested gluten is being unfairly blamed, with some saying the culprits could be other wheat proteins, yeast or pesticides. Another could be a group of carbohydrates known as Fodmaps (it stands for fermentable, oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols, and they are found in higher concentrations in a wide range of foods, including some fruit and vegetables, not just grains), which can cause bloating and wind.

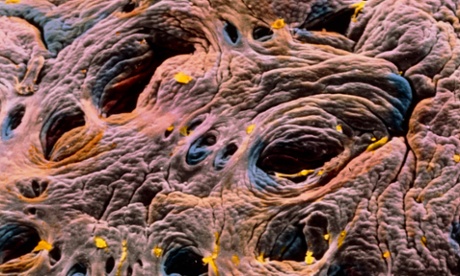

The number of people with coeliac disease "is undeniably something I have watched rise year on year for the last two decades," says gastroenterologist David Sanders ... coeliac disease in the intestinePhotograph: PR/PR

A study in 2013 by scientists at Monash University in Melbourne on people who had self-diagnosed as gluten intolerant found "no evidence of specific or dose-dependent effects of gluten in patients with NCGS" but found that a diet low in Fodmaps did improve symptoms. They also reported a high "nocebo" effect - those who had been put on the gluten-free arm of the diet in the double-blind study still reported symptoms. This prompted a number of articles with headlines such as "Science proves gluten sensitivity isn't real, people are just whiners". Sanders is far from ready to let gluten off the hook, and anyway, he says, it's not a war of opinions. "A gluten-free diet is a cousin of a [low] Fodmap diet. This is not a turf war ... The Fodmap work is really important, but I don't think it is a single fix."

What he is certain of is that there is a rise in coeliac disease. This could be because there is more awareness and diagnosis, but also because consumption of gluten-containing foods has increased. "Both in the Indian sub-continent and in China, as they are adopting a westernised diet they are developing coeliac disease. Before, it was a rice-based culture. Suddenly, as they bring in pizza, pasta, bread, they are seeing this. Another thing is, the number of wheats we have artificially cultivated in modern society have a higher gluten content than ancient grains. On a global scale the consumption of gluten is increasing and that comes at a price."

Around the 1960s, the intensification of agriculture gave rise to high-yielding varieties of wheat. Artificial fertiliser boosted production, and pesticides and fungicides were used to control pests and disease attracted to the fast-growing, bountiful crop. "That changed the nature of the grain and only in the last 10 or 15 years has it become clear that some of the protein structure - and gluten is a combination of wheat proteins - has changed," says Andrew Whitley, author of Bread Matters andco-founder of the Real Bread campaign. "Essentially there are bits of protein that have appeared because of the intensive breeding of grains for yield." (This has, however, been disputed by some studies.)

The second issue is modern, industrialised breadmaking. For most of humankind's breadmaking history, bread was similar to what we recognise as sourdough. Then the Chorleywood process, developed in 1961, revolutionised commercial baking - using high-speed machinery, and additives such as extra yeast, hard fats and enzymes, bread could be made quickly and cheaply; 80% of our bread is made this way. "We took the fermentation step out of baking," says Whitley. "Because a certain kind of profiteering mentality regarded time as money, they cut as much time out as possible." It meant "we were exposing people for the first time in history - and very large numbers of people in what constitutes a massive experiment on the British population - to proteins that previously would have been partially or completely digested by the fermentation system. Those are two massive changes in the way bread is made."

Another is that commercial bread manufacturers add extra gluten to loaves: "The role is purely technical - it's simply to make a fluffier, lighter loaf. To make it look as big and as good value as possible. My contention is that is also contributing to an excess of undigested gluten in the diet. Bread is not the only source of gluten, but it is the predominant way in which we consume it." The sad thing, Whitley adds with a small laugh, is that rather than looking at the cause, "the industry has spotted another opportunity to make money by making [gluten-free] products. The very people - the industrial millers and bakers - who foisted this problem on us are using it to make money in another sphere."

Rather than buying highly processed gluten-free bread products, Whitley advises finding a bakery "who you absolutely know is making their bread with proper fermentation" or learn to make your own. Maria Mayerhofer, whose company Bake With Maria runs baking classes, agrees. Furthermore, she sees potential problems in the substitutes: "A lot of the gluten-free bread you can buy, I always wonder if people know what's in that." Some gluten-free products are higher in fat and sugar to make them taste better, and have a host of other additives, including starches and binding agents. "People have been eating supermarket bread so they think it's bread altogether that's bad. Bread is not bad for you, it's a good source of nutrition - it has fibre and protein." Others have noted that avoiding wheat products can lead to deficiencies in nutrients such as folate.

Sanders, meanwhile, is concerned by the growing numbers who are cutting gluten out simply because they believe it is unhealthy - "What you might call the 'lifestylers'," he says. "The truth is there really isn't any clear evidence base." On the Jimmy Kimmel show, the comedian joked people went gluten-free because someone at their yoga class told them to - but it's also psychotherapists, celebrity health freaks, some nutritionists, bloggers and gluten-free product manufacturers who are pushing the "benefits" of a gluten-free diet. "To the lifestylers," says Sanders, "I would say don't think there is a health benefit to it because no such thing has been described." Even if people believe they have symptoms related to gluten, he says, "do not put yourself on a gluten-free diet". Rather, he advises people to go to their GP and have coeliac disease ruled out.

It is a "massive misconception" that gluten-free products are superior, says Sioned Quirke, a dietitian and spokesperson for the British Dietetic Association. "I'm seeing an increase of people coming to the clinic saying, 'I buy this gluten-free bread to help me lose weight' or 'it's better for me'. If you have coeliac disease, then it's essential that you have gluten-free products, but if you don't have an intolerance, for the general population, gluten-free products are really not required and they won't help you lose weight." She points out the high cost of going gluten-free unnecessarily. "It's a shame that a lot of people are wasting their money, when they could spend that money more wisely on having more fruit and vegetables."