Firas, left and Abu Ali, main chef at Barbar restaurant with a plate of Falafel and one of vegetables.In a country that has long faced the uncertainty of war and religious strife, you can bet on one thing. The doors that lead to Barbar's world-class kebabs will be open. The restaurant, arguably the most famous in Lebanon, has never closed since opening for business in 1979, the many fans of the establishment will tell you. The spits that rotate Barbar's succulent hunks of beef and chicken over slow-roasting flames didn't stop during the civil war that ended in 1990, management and employees say with pride. They say the grilling continued - 24/7 - even on the day that a rocket-propelled grenade struck the Beirut-based restaurant's entrance.While much of the country shut down during a devastating conflict with Israel in 2006, Barbar's employees still shaved off wafer-thin cuts of marinated shawarma meat to stuff into pita bread along with onions, parsley and garlic. After violently taking over Barbar's neighborhood in 2008, fighters linked to the country's Shiite Hezbollah movement even dropped by for scrumptious treats, employees say.

Barbar never turns away customers, said Bassem Abu Hamdan, 33, a police officer and customer. "It's always open. Always, always, always," he said. Lebanon's 4.2 million citizens are perhaps unusually picky about what they eat. After all, many Lebanese point out, their Arabic-Mediterranean cuisine of mezes and tangy salads is recognizable throughout the world. There is a culinary reputation to uphold, and although it's a tad gritty, Barbar certainly does that, fans say."It's so juicy," said Noura Karkajian, 54, as she shoved skewered chicken into her mouth on a recent evening. It's also affordable, she said. Her meal - which included coleslaw, fries and hummus - cost less than $10. Two years ago, CNN ranked Barbar first in a list of the world's best kebab places, coming ahead of restaurants in Israel, Iran and Greece. The news organization singled out Barbar's chicken shawarma - with its marinade of cardamom and cinnamon - as "the tastiest" of all offerings. For many Lebanese, Barbar resonates on a deeper level, symbolizing stability in a place so often shaken by unrest, said Amal Andary, a culture writer at Lebanon's Al-Akhbar newspaper. Recently, concern has mounted over fallout from civil war in next-door Syria. More than a million Syrians have taken refuge in Lebanon.

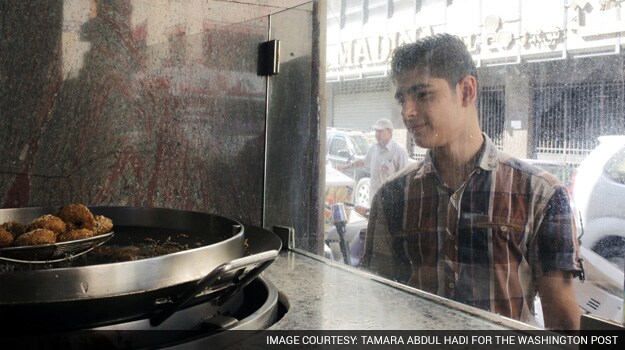

A young customer looks at the cooking falafel at Barbar restaurant. "It's an unshakable icon," Andary said of Barbar.

It's also massive, taking up almost an entire block in the capital's Hamra area. Surrounding the main restaurant are more than half a dozen Barbar shops that specialize in juices, sweets, sandwiches and specialty pizzas, called "manouche" in Arabic. (Barbar also operates a small branch near downtown.) Facades are faded. Waiters can be abrupt. And the no-frills picnic-table seating in the restaurant feels out of sync with Beirut's burgeoning market of trendy bistros that cater to wealthy, French-speaking elites.

But Barbar is popular. Poor. Rich. Famous. They all come. On Friday evenings, finding a seat at the restaurant can feel as frustrating as standing in line at a VIP nightclub.

"You can't believe the pressure I'm working under!" Mohammed Rezik, 46, a waiter, said as he served a crush of patrons on a recent evening. Mohammed Hussein, 47, the mustachioed head of Barbar's falafel department, boasted about having served Arabic singers and movie stars, including Egyptian actor Adel Emam.

"They all come here," he said. "It's normal."

Barbar's origins trace back to its sexagenarian founder, Mohammed Ghaziri. With a fifth-grade education and the clothes on his back, a 17-year-old Ghaziri took a job on a Greek shipping vessel in the late 1960s, touring the world and its restaurants. Returning to Lebanon a decade later with cash in hand, he opened a small manouche shop. Every few years since then, Ghaziri expanded, said his son, 33-year-old Ali Ghaziri, who is now co-owner with a brother of what has become the Barbar Empire. The only time the establishment failed to make money was when the elder Ghaziri attempted to turn the restaurant into a place for fine dining, Ali Ghaziri said.

"That didn't work out, so he went back to his roots," Ghaziri said of his father, who is retired and now spends much of his time on a yacht.

Reaching back to the restaurant's roots meant catering to the rich, poor, and Lebanon's diverse and feuding religious groups. During the 15-year civil war, fighters representing many factions would take breaks at the restaurant to fill up on grilled meats, salads and pizzas, Ali Ghaziri said. To protect patrons, the restaurant erected a 10-foot-high sandbag wall between the entrance and the adjacent street.

"There was fighting all around," said Ghaziri, who noted that the grenade attack killed one person.

Nowadays, Beirut manages a shaky calm. Barbar's employees seem more concerned about a crisis over garbage collection that has caused trash to pile up on the capital's streets. One pile isn't far from the restaurant. Customers seem unfazed. Hussein el-Soud, 29, visited recently from his home town of Cairo. He just had to dine at Barbar, he said.

"All my friends said I have to eat here," Soud said while devouring a plate of beef shawarma.

"It's delicious."

(c) 2015, The Washington Post

Barbar never turns away customers, said Bassem Abu Hamdan, 33, a police officer and customer. "It's always open. Always, always, always," he said. Lebanon's 4.2 million citizens are perhaps unusually picky about what they eat. After all, many Lebanese point out, their Arabic-Mediterranean cuisine of mezes and tangy salads is recognizable throughout the world. There is a culinary reputation to uphold, and although it's a tad gritty, Barbar certainly does that, fans say."It's so juicy," said Noura Karkajian, 54, as she shoved skewered chicken into her mouth on a recent evening. It's also affordable, she said. Her meal - which included coleslaw, fries and hummus - cost less than $10. Two years ago, CNN ranked Barbar first in a list of the world's best kebab places, coming ahead of restaurants in Israel, Iran and Greece. The news organization singled out Barbar's chicken shawarma - with its marinade of cardamom and cinnamon - as "the tastiest" of all offerings. For many Lebanese, Barbar resonates on a deeper level, symbolizing stability in a place so often shaken by unrest, said Amal Andary, a culture writer at Lebanon's Al-Akhbar newspaper. Recently, concern has mounted over fallout from civil war in next-door Syria. More than a million Syrians have taken refuge in Lebanon.

A young customer looks at the cooking falafel at Barbar restaurant. "It's an unshakable icon," Andary said of Barbar.

It's also massive, taking up almost an entire block in the capital's Hamra area. Surrounding the main restaurant are more than half a dozen Barbar shops that specialize in juices, sweets, sandwiches and specialty pizzas, called "manouche" in Arabic. (Barbar also operates a small branch near downtown.) Facades are faded. Waiters can be abrupt. And the no-frills picnic-table seating in the restaurant feels out of sync with Beirut's burgeoning market of trendy bistros that cater to wealthy, French-speaking elites.

But Barbar is popular. Poor. Rich. Famous. They all come. On Friday evenings, finding a seat at the restaurant can feel as frustrating as standing in line at a VIP nightclub.

"You can't believe the pressure I'm working under!" Mohammed Rezik, 46, a waiter, said as he served a crush of patrons on a recent evening. Mohammed Hussein, 47, the mustachioed head of Barbar's falafel department, boasted about having served Arabic singers and movie stars, including Egyptian actor Adel Emam.

"They all come here," he said. "It's normal."

Barbar's origins trace back to its sexagenarian founder, Mohammed Ghaziri. With a fifth-grade education and the clothes on his back, a 17-year-old Ghaziri took a job on a Greek shipping vessel in the late 1960s, touring the world and its restaurants. Returning to Lebanon a decade later with cash in hand, he opened a small manouche shop. Every few years since then, Ghaziri expanded, said his son, 33-year-old Ali Ghaziri, who is now co-owner with a brother of what has become the Barbar Empire. The only time the establishment failed to make money was when the elder Ghaziri attempted to turn the restaurant into a place for fine dining, Ali Ghaziri said.

"That didn't work out, so he went back to his roots," Ghaziri said of his father, who is retired and now spends much of his time on a yacht.

Reaching back to the restaurant's roots meant catering to the rich, poor, and Lebanon's diverse and feuding religious groups. During the 15-year civil war, fighters representing many factions would take breaks at the restaurant to fill up on grilled meats, salads and pizzas, Ali Ghaziri said. To protect patrons, the restaurant erected a 10-foot-high sandbag wall between the entrance and the adjacent street.

"There was fighting all around," said Ghaziri, who noted that the grenade attack killed one person.

Nowadays, Beirut manages a shaky calm. Barbar's employees seem more concerned about a crisis over garbage collection that has caused trash to pile up on the capital's streets. One pile isn't far from the restaurant. Customers seem unfazed. Hussein el-Soud, 29, visited recently from his home town of Cairo. He just had to dine at Barbar, he said.

"All my friends said I have to eat here," Soud said while devouring a plate of beef shawarma.

"It's delicious."

(c) 2015, The Washington Post

Advertisement