The American subjects switched to a low-fat, high-fibre diet based on that of rural Africans in KwaZulu-Natal. Photograph: brianafrica / Alamy/AlamyTests on subjects who swapped a fatty, meat-heavy diet for foods rich in beans and vegetables found a drop in biological markers for cancer in just two weeks.Swapping a western diet for traditional African meals may reduce the risk of colon cancer, scientists have found.

Tests on African Americans who replaced their fatty, meat-heavy diets with rural African foods rich in beans and vegetables found that in just two weeks, biological markers pointed to a drop in their disease risk.

Colon cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the UK and the second leading cause of cancer death in the west. Globally, a million people are diagnosed with the disease each year.

African Americans are more than 100 times more likely to develop colon cancer than rural Africans, and the difference in diets is thought to be a major reason. The results suggest high-fibre diets could have a dramatic effect on colon cancer among populations most at risk.

The scientists began by studying the diets of 20 African Americans from Pittsburgh and 20 rural Africans in KwaZulu-Natal in their homes. The African Americans ate two to three times more fat and animal protein than the rural Africans did, and far less dietary fibre.

The researchers then ran tests on the microbes living in the guts of the two groups. They found that the American and African diets were associated with very different populations of gut microbes. The rural Africans had more carbohydrate-fermenting bugs, and others that produced a chemical called butyrate. The Americans had more microbes that break down bile acids. Colonoscopies revealed polyps - which can sometimes mature into tumours - in nine of the Americans, but none of the rural Africans.

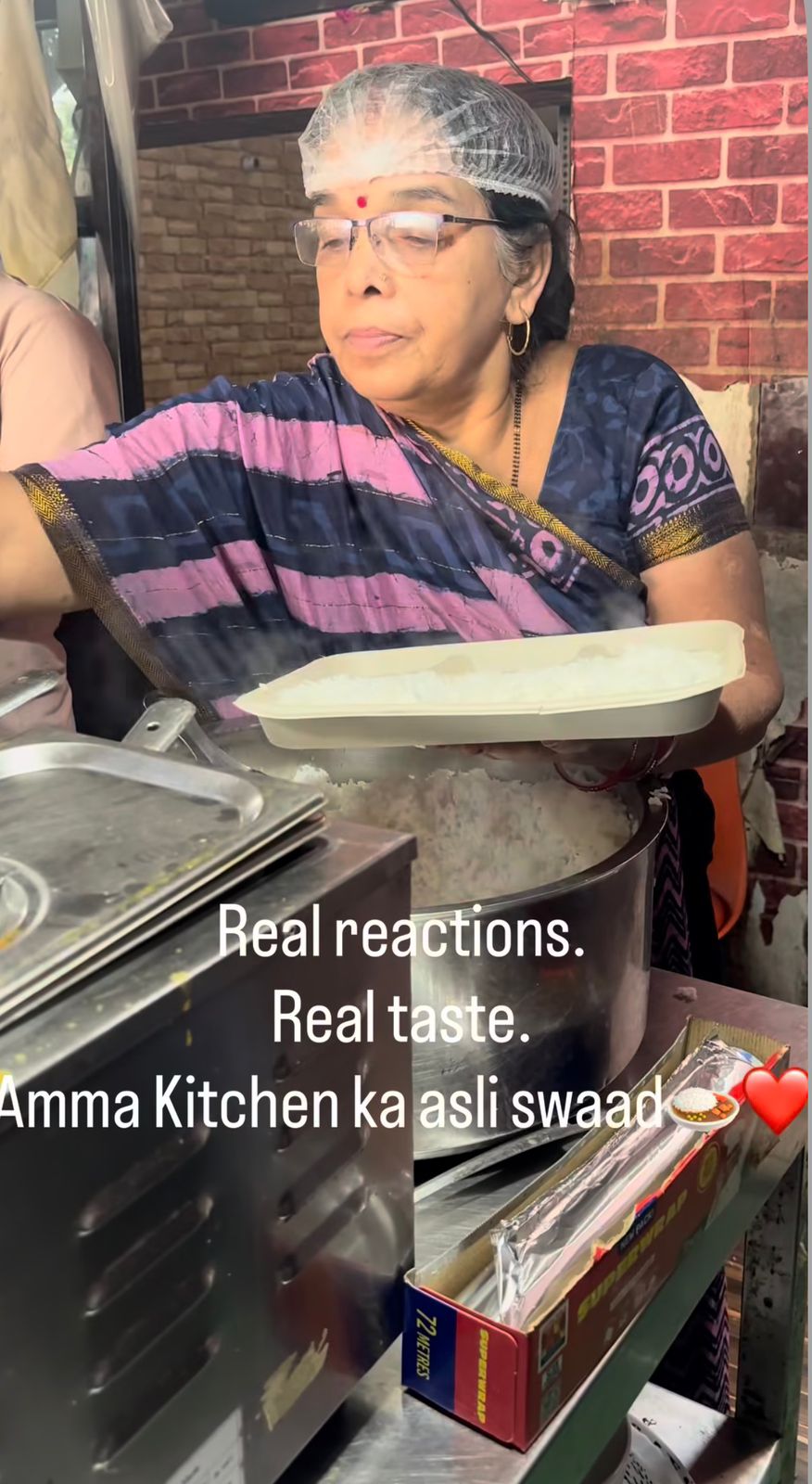

The scientists next invited the two groups to stay at local centres, where their diets were switched over for a fortnight. Instead of their traditional high-fibre meals, the rural Africans consumed a high-fat, high-protein diet of sausages, hash browns, burgers and fries. Meanwhile, the African Americans switched to a low-fat, high-fibre diet including corn fritters, mango slices, bean soup and fish tacos.

At the end of the two weeks, the team from the University of Pittsburgh and Imperial College London found that the African Americans had less inflamed colons than before, and a reduction in biological markers for cancer. The only downside of the diet seemed to be an excess of wind.

While the African Americans seemed to fare better on the high-fibre meals, the rural Africans appeared to do worse on the western diet. Tests on material taken from their guts suggested that their risk of colon cancer had risen.

“We were astounded at the degree of change. We thought we’d find a few changes here and there when they swapped diets, but this mirror image was totally unexpected,” said Stephen O’Keefe, who led the study, in Nature Communications. The results suggest it may never be too late for people to change their diets to reduce the risk of colon cancer, he added.

The changes in cancer risk coincided with dramatic changes in gut microbes in the two groups. On the rural African high-fibre diet, gut microbes produced more butyrate, a chemical that has anti-cancer properties. Meanwhile, on the high-fat western diet, the microbes produced more bile acids, which may increase cancer risk.

Research has shown before that high-fibre diets are linked to reduced colon cancer risk, but how fibre, which passes undigested into the colon, might help has been unclear. The Pittsburgh study suggests that diet may affect cancer risk by changing the populations of microbes thriving in the gut and the chemicals they churn out.

The scientists cannot tell for sure that the change in diet would have led to more cancer in the African group or less in the American group. That would only become clear if they swapped diets for years. But Jeremy Nicholson, a senior co-author on the study at Imperial College, said there was good evidence that the changes they detected were reliable signs of cancer risk.

“What is startling to me is how profoundly the microbes, metabolism and cancer risk factors change in just two weeks of diet change. It means to me that diet and environment and microbial genes are likely to be much more important than individual human genes in determining individual colonic cancer risks,” he said.

“Certainly it shows that your possible fate is not just determined by the genetic dice at birth. How you roll the dice in the game is probably more important,” he added.