When David Schillace told his friends and family in 2010 that he planned to quit his six-figure-salary job in sales and marketing, cash in his 401(k) retirement plan and start a new career selling a blend of Mexican and barbecue food out of a truck on the streets of Manhattan, there was stunned silence. Then came the tears.

"My mom cried - she literally cried - and said: 'What are you doing? You left your $150K corporate job for a truck?'" Schillace recalled. Though crushed by the reaction, he pressed ahead with his dream.

Today, Schillace and his partner, Thomas Kelly, own three Mexicue restaurants, employ about 200 people and have the backing of Sandy Beall, who founded Ruby Tuesday restaurants in 1972, and who stepped down as CEO of that chain in 2012.

Mexicue's revenue topped $6 million in 2014, up from $500,000 in its first year in 2010. Plans are underway to open at least two new restaurants a year in hopes of generating at least $20 million in annual revenue by 2017.

Ultimately, the two founders would like to follow in the footsteps of Shake Shack, which also started as a small vendor in a park in Manhattan and wound up with a valuation in excess of $1 billion when it went public this year. "Seeing Danny Meyer stand on the New York Stock Exchange, ringing that bell - of course, that's inspiring," Schillace said, referring to the Shake Shack founder and restaurateur. "That's what we want to do."

The story of how a fast-food truck becomes a brick-and-mortar restaurant with chain ambitions is a complicated one.

Mexicue sits in the fastest-growing segment of the restaurant industry. Its focus is on using fresh, all-natural ingredients, buying locally when possible, using meat that has been produced without antibiotics or hormones, cooking from scratch and spicing it up. The results, served quickly and affordably, appeal to the so-called eating healthy crowd. Chipotle Mexican Grill is a standout in this niche.

Traffic to fast-casual restaurants like Chipotle has climbed 7 to 9 percent each year, even at the height of the recession, since 2009, according to Bonnie Riggs, a restaurant analyst at the NPD Group, a market information and advisory firm.

By contrast, traffic to conventional fast-food outlets was flat, while traffic to midtier family restaurants declined in the same period.

Schillace exhibited some entrepreneurial inclinations early on. Born in Brooklyn, he grew up in Holmdel, New Jersey, where he sold lemonade and baked goods to neighbors as a youngster. He studied business at Arizona State University, graduating with a bachelor's in business administration in 2004. He then moved to New York, where he took sales jobs at several Fortune 500 companies, including T-Mobile, Forest Pharmaceuticals and Integra LifeSciences.

His career took a sharp turn in 2009. While visiting a college friend in Los Angeles, he discovered a food truck revolution, where people lined up for blocks to buy food from Kogi-branded trucks. It was an "aha" moment for Schillace, who decided to bring the concept to New York. "It was something I could start without having to raise a million dollars," he said. "I thought I could pull it off with $50,000."

Next, he needed a partner and chef. So, back in New York, he approached a friend, Thomas Kelly, who had hosted weekly dinner parties and served elaborate meals at Thanksgiving. "I always had this entrepreneurial itch like David," Kelly said.

Kelly, born in Minneapolis in 1978, developed a passion for cooking when he was a child. He would toil in the kitchen alongside his mother and grandmother, and help his father fire up the barbecue. Before graduating from Colorado State with a bachelor's in humanities in 2000, he loved experimenting in the kitchen and cooking for roommates. Though he didn't go to culinary school, after moving to New York in 2001, Kelly worked at a marketing job by day and trained as an unpaid intern at the restaurants Craft and Hearth by night, where he honed his kitchen skills. (He also got an MBA from the New York University Stern School of Business in 2013.)

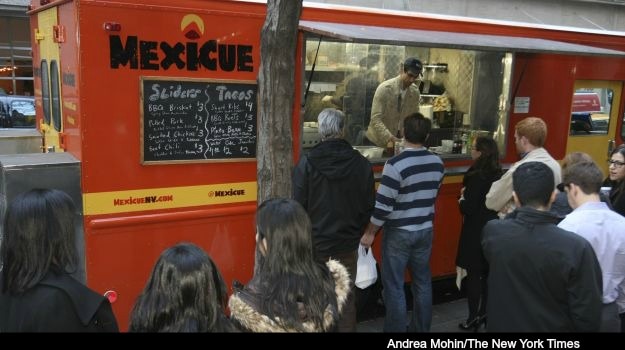

In 2010, with $80,000 in their pockets, Schillace and Kelly bought a food truck off eBay, drew up a Mexican-barbecue menu and were on their way. Schillace said there was only one other branded food truck in Manhattan at the time. "It was like the Wild West," he said, adding that they could park wherever they wanted. But by 2011, competition had soared with about 75 branded trucks crowding into the market, which led to city crackdowns. Retail operators often complained that their profits were threatened by the presence of food trucks.

Schillace would arrive early and use his Jeep Cherokee to hold a spot on the street for the truck. One day, about 15 angry street vendors, unhappy that Mexicue was taking away their business, surrounded the Jeep and began pounding on the windows, demanding that Schillace leave the area. Schillace, though scared, locked the doors and waited for the truck to arrive.

Sometimes when a coveted spot was occupied by a repair truck, Schillace would call the phone number listed on the truck. Posing as a city employee, he would demand that the company move the truck immediately or it would be ticketed. "I'd see these repair guys running out of offices to move their trucks, and I'd just drive into the space when they left," he said, laughing.

In 2011, inspired in part by a snowstorm that hurt the food truck business, the partners opened their first brick-and-mortar restaurant, a 450-square-foot space on Seventh Avenue that offered both takeout and a small dining area. (The truck was relegated to music festivals and special events.)

As Mexicue's popularity grew, Schillace approached investors to raise about $500,000 to open a second restaurant - a 1,200-square-foot space on Broadway. That was when Sandy Beall, who founded Ruby Tuesday and spent 40 years building it into an international brand, came onboard.

"I've invested a lot in Mexicue because I believe in what we're doing," said Beall, who holds a 25 percent ownership stake in Mexicue. A third restaurant - a 2,400-square-foot space at 225 Fifth Ave. - opened in April.

How often a food truck becomes a restaurant is unclear, but Julia Gallo-Torres, of Mintel, the marketing research firm, said it was probably an anomaly rather than the norm.

"A lot of food truck startups just remain food trucks," and often the owners burn out after a period of time, she said. "Food trucks are not sustainable because of the lifestyle. They tend to be owned by people who have to work and do all of the jobs that are involved there. It's not something they want to do long-term."

And making the transition to a brick-and-mortar restaurant presents other challenges. "It's a cheap way to get into the restaurant business," she said. But many don't have the business wherewithal to start and run a restaurant. Having a business background and having the backing of an experienced restaurant owner greatly improve the chances of success, she said.

Does Beall share the younger Mexicue founders' zeal that the brand could turn into a major player in the restaurant industry and someday go public?

"Everybody at that age thinks that," Beall said, laughing. "It could. But we take things one store at a time. I'm not worried if we have four or 100. Just do it right one day at a time and you'll make plenty of money."© 2015 New York Times News Service