A spanner in the works for Bradley Cooper's new film, Chef, in the flabby shape of Jon Favreau's latest offering, erm, Chef. Favreau's enjoyable if schmaltzy flick pipped Cooper's, leaving Cooper's to be deed-polled to the none-too-catchy Adam Jones. If anything marks the recent surge in gastro-nerdery from the niche to the middle-ground it's the arrival of two films called Chef.

Granted, Cooper's Chef, or rather, Adam Jones, hasn't started shooting yet, but in Hollywood terms this is fairly quick succession. The film industry has licked a salty finger, stuck it skyward, and ascertained that what we want to see on the big screen is food. Big, pornographic plates of food. Emmental-laden as Chef was, a sybarite is unlikely to have been able to resist the graphic images of oil squizzing over pork and pickles, sensually spooned sauce on glossy meat, and the most outrageously amplified audio of a man eating a toasted cheese sandwich you are ever likely to hear.

Moreover, to appeal to the food geeks of this world - which, if the execs of Hollywood are right, is all of us - these films are bringing in some big names as consultants. "Food truck pioneer" Roy Choi oversaw every culinary aspect of Chef, sending Favreau to cooking school and throwing him into the line in several of his own kitchens. Meanwhile, the stars of Adam Jones spent time under the gun-metal gaze of Marcus Wareing learning to chop like a pro.

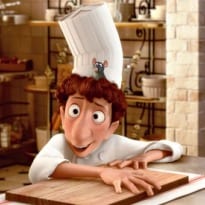

Films set to the backdrop of food are nothing new, nor is thorough, near-obsessive research for a role - just ask Dick Van Dyke (or do I mean Daniel Day-Lewis?) - and yet this new meticulous drive for the cooking in films to be echt seems to be another important marker in arcane foodism's move into the mainstream. Traditionally, food cinema has been far more conventional and in keeping with the accepted view of restaurants. Take Ratatouille, on which chef Thomas Keller was a consultant. Its plausible brigade, its volatile chef, its pre-packaged food, the knowing wink of a waiter on roller blades, and a Proustian moment to finish it all off, all conform to how we feel restaurants should be. Sure, the kitchen is improbably stunning, the chef perhaps a little too caricatured, and, well, it's about a cooking rat, but the picture rings true at least with a cliched ideal.

Similarly, the 1996 film Big Night, while never feeling like an overwrought manifestation of a real restaurant, nevertheless portrays a level of authenticity with which it is easy to empathise - the tumbleweed quiet of a neighbourhood restaurant, the false promise of the arrival of a celebrity to help turn your humble gaff into the next Chiltern Firehouse, and the halfwit punter who wants a side of spaghetti with their risotto. Stanley Tucci's maître d' grins and bears it; chef, not so much ("she's a criminal, I want to talk to her").

There have been shockers, too. Love's Kitchen with its excruciating Gordon Ramsay cameo, or Catherine Zeta-Jones's No Reservations, about which the critics had more than a few. But then there's Eat Drink Man Woman and Babette's Feast and countless other films in which stunning food provides texture and context for a good story.

But we're all foodies now, and thus food cinema moves with the times. Perhaps Babette's Feast would have been different had Twitter existed in 1987. Maybe Remy the Rat would have been an Instagram sensation. We'll never know. What is certain is that the polish and shine of modern food imagery is becoming ever more widespread. No longer can we only find our food porn in glossy magazines, grainy phone images or snatched lunchtime sessions on YouTube. Gastro porn has hit the big screen. It's all rather exciting, but then again, sometimes I'm just as happy with a plate of ratatouille.

What are your favourite food moments in film?

Ratatouille ... had chef Thomas Keller as a consultant.