An undated handout photo of Jacques Pepin in his Connecticut studio.Jacques Pépin, who will turn 80 on Dec. 18, exudes an air of perennial youth. Having worked his way up the rungs of rigorous Paris kitchens before coming to New York, he became the youngest in a circle of influential cooks (including Julia Child, Pierre Franey, James Beard and Craig Claiborne) who helped ignite a new enthusiasm in the United States for food and dining. In this essay, taken from a piece Pépin wrote for a birthday celebration in October, he looks back to his earliest years.There is something evanescent, temporary and fragile about food. You make it, it goes, and what remains are memories.

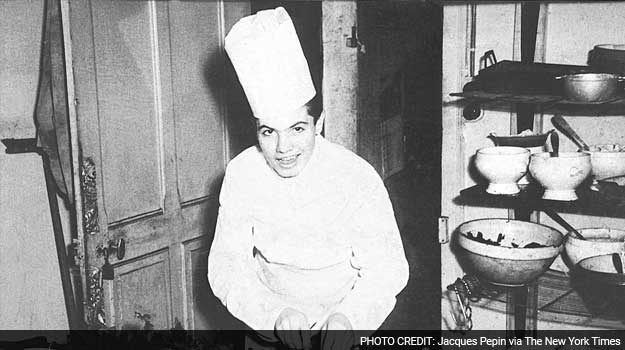

But these memories of food are very powerful. In the words of George Bernard Shaw, “There is no love more sincere than the love of food.” Lin Yutang, a Chinese philosopher, tells us that “Patriotism is the love of the dishes of our childhood.” Yes, the dishes of our childhood stay with us forever.My earliest memories of food go back to the time of the Second World War. My mother took me to a farm for the summer school vacation when I was 6 years old with the knowledge that I would be lodged and fed there. I cried after she left and felt sad, but the fermière took me to the barn to milk the cow. That warm, foamy glass of milk is my first true memory of food and shaped the rest of my life.I also remember as a young child helping my mother in our family restaurant, washing bottles for the wine and peeling potatoes. I began my formal culinary apprenticeship in 1949 at age 13 in the kitchens of the Grand Hôtel de l’Europe in my hometown, Bourg-en-Bresse, near Lyon.Going back as far as my memory can take me, I see a kitchen in my vision of my mother, my aunts, my cousins, and I visualize a specific dish for each of them.For my mother, what comes to mind first are the small fingerling potatoes, fresh out of the garden, with skin that would slide off when rubbed by your fingers. These potatoes were simply sautéed in butter to a crisp exterior and served with an escarole salad dressed with mustard, vinegar and peanut oil scented with garlic.I recall that in my Aunt Hélène’s chicken in cream sauce with morels, she actually used dried gyromitras, the false morels with intense flavor that are designated as poisonous in most books on mycology. These never did any harm to us. Remembering my Aunt Aimée brings to mind a shoulder veal roast made in a cast-iron pot. Browned in butter and flavored with onion, it created incredibly flavored natural juices that I have never been able to duplicate.Remembering my cousin Merret reminds me of her amazing chicken liver flan served with a tomato concassé, olives and mushrooms. I can envision my cousin Christiane with her incredible fresh white cheese (fromage blanc), covered with the thickest, unctuous cream and flavored with chives and garlic, and I see my niece Nathalie serving her boudin noir, or black pudding, with buttered sautéed apples and fresh mashed potatoes.I can visualize myself with my father in the cellar drawing wine, tending the garden with my brother, mushrooming with friends or cooking with my wife, Gloria, or my friend Jean-Claude.My cultural identity is always related to food, and that gastronomic culture includes a whole set of rules and habits that define my way of life. In this culture there are rituals, like the special events of playing boules, having a picnic or going frogging or mushrooming. These rituals are made up of traditions, which are the ways rituals are implemented, such as the preparation of traditional recipes and specific ways of doing things.The majority of people can live well with 20 or 30 recipes and, in fact, all of their family traditions and rituals are expressed through those recipes. For most people, the dishes that matter are the dishes that have been cooked with love, dishes that are part of a family’s structure, passed down from a grandmother, mother, spouse, aunt, uncle or cousin. Those dishes remain much more embedded in our taste memory than the recipes and dishes of great restaurants, even for a professional cook like me.Dr. Urbino, a character in “Love in the Time of Cholera,” by Gabriel García Márquez, is served a dish that has been cooked by an indifferent new housekeeper. He pushes it back uneaten and declares, “This dish has been cooked without love.”In the famous passage where he writes about the small scalloped cake named madeleine<em>, </em>Proust in his “Remembrance of Things Past” develops his theory of “affective memory.” The affective memory, or memory of the senses — smell, taste, touch, hearing and eyesight — is different from conventional memory.If I reflect on a specific moment of my life, my brain can take me there and, hopefully, I will remember the moment, the occasion and the people. Affective memory works in a different way. When Proust dips his small madeleine in his tea on that fateful afternoon, he may have been talking about the events of the day, but suddenly the taste of the cake troubles and disturbs him.Tasting it again, he realizes that this specific taste reminds him of the small cake his aunt always had for him when, as a child, he spent his summers in the small town of Combray on the coast of Normandy. By association of ideas, he sees the teacup, the kitchen, the cook, the garden and, as he says, eventually the whole town of Combray comes out of his cup of tea. An undated handout photo that appeared in a newspaper at the time of Jacques Pepin, age 16, preparing food for a Fireman's Ball. In an essay, the now 80-year-old chef, the youngest in a circle of influential cooks (including Julia Child, Pierre Franey, James Beard and Craig Claiborne) who helped ignite a new enthusiasm in the U.S. for food and dining, looks back to his earliest years

An undated handout photo that appeared in a newspaper at the time of Jacques Pepin, age 16, preparing food for a Fireman's Ball. In an essay, the now 80-year-old chef, the youngest in a circle of influential cooks (including Julia Child, Pierre Franey, James Beard and Craig Claiborne) who helped ignite a new enthusiasm in the U.S. for food and dining, looks back to his earliest years

With the memories of my brain, it may take me a few minutes to summon up and review a specific event of my life. Conversely, the affective memory is immediate and very powerful, often overwhelming. I may be walking in the woods with my dog, not thinking about anything in particular, when the smell of a wild mushroom brings me back instantly and powerfully to my childhood and hunting mushrooms in the woods with my father or brother.Affective memory assails you when you least expect it and is felt more profoundly than conventional memory. These memories are essential for the cook, the food critic and the writer. They enrich your day-to-day life and your relationships with your family and friends. When I smell or see certain recipes, I also see my family — wife, daughter, brothers, mother or friends; there is no separating food from the visual. When I eat a small spring salad, I see my father’s garden or my gardens in upstate New York or Connecticut.Other things embedded in my food memories are markets and seasons. The Marché St.-Antoine, along the Saône in Lyon, or the market in Antibes, where I remember a little woman from whom I bought maybe the best apricot jam I ever had in my life. I recall the Wednesday market in Bourg-en-Bresse, and markets in Provence: Arles, Avignon and St.-Rémy.My recipes are always closely linked to my markets in Madison, the Connecticut town where I live, as well as Bishop’s in the neighboring town of Guilford, Ferraro’s in New Haven and the little farm nearby where Nathalia, a vibrant young woman from Jamaica, has the best eggs you could find anywhere. I go to a farm on the Hammonasset Connector to get fresh peas and corn in the summer, and the Lobster Landing in Clinton, where I buy lobsters.When I think of all the markets I have been to in this world — from the fish markets in Tokyo and Portugal, and the West African markets of Dakar, as well as markets in Marrakesh, Fez or in Progreso in the Yucatán Peninsula, my travels are always associated with local products and restaurants. I’ll never forget the fish restaurant on the beach in Málaga, Spain, where all the freshest seafood, just off the boat, is cooked on an immense grill fueled with the roots of olive trees and where the grilled sardines are unforgettable.I visualize markets throughout the year, according to season and specific dishes that celebrate the seasons. In the spring, there is a sweet smell to the earth when I plant my garden, and when those tiny seeds start emerging from the ground, it is still a miracle every year. Nothing compares each April to the wild dandelion salad greens that I pick along the edge of the road, the tiny fresh peas from a nearby farm and sweet baby carrots.In summer, I like drowsing in the hot sun or walking in the cool grass, conjuring up mushrooms in the woods and picking up little fish along the shore in Madison to fry whole, like French fries. I dream of steamed lobster, juicy and sugary corn, creamy new potatoes and picnics with fried chicken, lukewarm plum tomatoes, and cool white wine along the Hammonasset River.There is a sweetness and gentleness to the fall. I love the fragrant smell of apple tarts, making cider, roasting a duck with sweet potatoes, the bursting yellow and red of the maple trees, the tanginess of the Concord grapes, and, finally, the turkey of Thanksgiving, my favorite holiday.Winter in America will always call to mind the brilliant sun and blue sky, with piercing cold and crisp air and the smell of chestnuts in the streets of New York City when I first arrived in 1959.In Connecticut, winter is the smell of burning wood in the fireplace, comforting bean stew and split pea with ham soup, cheese fondue and the feasts of the holidays, which we celebrate with oysters, capon or goose, foie gras and chocolate truffles. This is the best time for small children, and I can see myself and my daughter, Claudine, making caramel candies in the snow.I recall lazy afternoons with a good book by the fireplace, and long walks with my dog along the deserted beach battered by cold wind under a gray and black sky.The greatest taste for me may be a perfect crunchy baguette slathered generously with the very best sweet butter, and the greatest dessert, besides dark, bitter chocolate, may be the succulent apricot or strawberry jams made with very ripe fruits and spread thickly on pieces of warm brioche.My greatest ritual is sitting every night at the dining-room table with my wife and sharing our meal and one, sometimes two, bottles of wine and discussing the events of the day. Throughout the last five decades, this daily ritual has been ingrained so profoundly within us that we could not live without it, and this is how food memories are made.In the words of Voltaire, “Imagine how tiresome it would be to have to eat three times a day if God had not made it a pleasure as well as a necessity.” I hope that you enjoyed traveling with me along my memory lane, and that you will share your table in a daily ritual with your loved ones and enjoy life to the fullest.Happy cooking!© 2015, The New York Times News Service

But these memories of food are very powerful. In the words of George Bernard Shaw, “There is no love more sincere than the love of food.” Lin Yutang, a Chinese philosopher, tells us that “Patriotism is the love of the dishes of our childhood.” Yes, the dishes of our childhood stay with us forever.My earliest memories of food go back to the time of the Second World War. My mother took me to a farm for the summer school vacation when I was 6 years old with the knowledge that I would be lodged and fed there. I cried after she left and felt sad, but the fermière took me to the barn to milk the cow. That warm, foamy glass of milk is my first true memory of food and shaped the rest of my life.I also remember as a young child helping my mother in our family restaurant, washing bottles for the wine and peeling potatoes. I began my formal culinary apprenticeship in 1949 at age 13 in the kitchens of the Grand Hôtel de l’Europe in my hometown, Bourg-en-Bresse, near Lyon.Going back as far as my memory can take me, I see a kitchen in my vision of my mother, my aunts, my cousins, and I visualize a specific dish for each of them.For my mother, what comes to mind first are the small fingerling potatoes, fresh out of the garden, with skin that would slide off when rubbed by your fingers. These potatoes were simply sautéed in butter to a crisp exterior and served with an escarole salad dressed with mustard, vinegar and peanut oil scented with garlic.I recall that in my Aunt Hélène’s chicken in cream sauce with morels, she actually used dried gyromitras, the false morels with intense flavor that are designated as poisonous in most books on mycology. These never did any harm to us. Remembering my Aunt Aimée brings to mind a shoulder veal roast made in a cast-iron pot. Browned in butter and flavored with onion, it created incredibly flavored natural juices that I have never been able to duplicate.Remembering my cousin Merret reminds me of her amazing chicken liver flan served with a tomato concassé, olives and mushrooms. I can envision my cousin Christiane with her incredible fresh white cheese (fromage blanc), covered with the thickest, unctuous cream and flavored with chives and garlic, and I see my niece Nathalie serving her boudin noir, or black pudding, with buttered sautéed apples and fresh mashed potatoes.I can visualize myself with my father in the cellar drawing wine, tending the garden with my brother, mushrooming with friends or cooking with my wife, Gloria, or my friend Jean-Claude.My cultural identity is always related to food, and that gastronomic culture includes a whole set of rules and habits that define my way of life. In this culture there are rituals, like the special events of playing boules, having a picnic or going frogging or mushrooming. These rituals are made up of traditions, which are the ways rituals are implemented, such as the preparation of traditional recipes and specific ways of doing things.The majority of people can live well with 20 or 30 recipes and, in fact, all of their family traditions and rituals are expressed through those recipes. For most people, the dishes that matter are the dishes that have been cooked with love, dishes that are part of a family’s structure, passed down from a grandmother, mother, spouse, aunt, uncle or cousin. Those dishes remain much more embedded in our taste memory than the recipes and dishes of great restaurants, even for a professional cook like me.Dr. Urbino, a character in “Love in the Time of Cholera,” by Gabriel García Márquez, is served a dish that has been cooked by an indifferent new housekeeper. He pushes it back uneaten and declares, “This dish has been cooked without love.”In the famous passage where he writes about the small scalloped cake named madeleine<em>, </em>Proust in his “Remembrance of Things Past” develops his theory of “affective memory.” The affective memory, or memory of the senses — smell, taste, touch, hearing and eyesight — is different from conventional memory.If I reflect on a specific moment of my life, my brain can take me there and, hopefully, I will remember the moment, the occasion and the people. Affective memory works in a different way. When Proust dips his small madeleine in his tea on that fateful afternoon, he may have been talking about the events of the day, but suddenly the taste of the cake troubles and disturbs him.Tasting it again, he realizes that this specific taste reminds him of the small cake his aunt always had for him when, as a child, he spent his summers in the small town of Combray on the coast of Normandy. By association of ideas, he sees the teacup, the kitchen, the cook, the garden and, as he says, eventually the whole town of Combray comes out of his cup of tea.

With the memories of my brain, it may take me a few minutes to summon up and review a specific event of my life. Conversely, the affective memory is immediate and very powerful, often overwhelming. I may be walking in the woods with my dog, not thinking about anything in particular, when the smell of a wild mushroom brings me back instantly and powerfully to my childhood and hunting mushrooms in the woods with my father or brother.Affective memory assails you when you least expect it and is felt more profoundly than conventional memory. These memories are essential for the cook, the food critic and the writer. They enrich your day-to-day life and your relationships with your family and friends. When I smell or see certain recipes, I also see my family — wife, daughter, brothers, mother or friends; there is no separating food from the visual. When I eat a small spring salad, I see my father’s garden or my gardens in upstate New York or Connecticut.Other things embedded in my food memories are markets and seasons. The Marché St.-Antoine, along the Saône in Lyon, or the market in Antibes, where I remember a little woman from whom I bought maybe the best apricot jam I ever had in my life. I recall the Wednesday market in Bourg-en-Bresse, and markets in Provence: Arles, Avignon and St.-Rémy.My recipes are always closely linked to my markets in Madison, the Connecticut town where I live, as well as Bishop’s in the neighboring town of Guilford, Ferraro’s in New Haven and the little farm nearby where Nathalia, a vibrant young woman from Jamaica, has the best eggs you could find anywhere. I go to a farm on the Hammonasset Connector to get fresh peas and corn in the summer, and the Lobster Landing in Clinton, where I buy lobsters.When I think of all the markets I have been to in this world — from the fish markets in Tokyo and Portugal, and the West African markets of Dakar, as well as markets in Marrakesh, Fez or in Progreso in the Yucatán Peninsula, my travels are always associated with local products and restaurants. I’ll never forget the fish restaurant on the beach in Málaga, Spain, where all the freshest seafood, just off the boat, is cooked on an immense grill fueled with the roots of olive trees and where the grilled sardines are unforgettable.I visualize markets throughout the year, according to season and specific dishes that celebrate the seasons. In the spring, there is a sweet smell to the earth when I plant my garden, and when those tiny seeds start emerging from the ground, it is still a miracle every year. Nothing compares each April to the wild dandelion salad greens that I pick along the edge of the road, the tiny fresh peas from a nearby farm and sweet baby carrots.In summer, I like drowsing in the hot sun or walking in the cool grass, conjuring up mushrooms in the woods and picking up little fish along the shore in Madison to fry whole, like French fries. I dream of steamed lobster, juicy and sugary corn, creamy new potatoes and picnics with fried chicken, lukewarm plum tomatoes, and cool white wine along the Hammonasset River.There is a sweetness and gentleness to the fall. I love the fragrant smell of apple tarts, making cider, roasting a duck with sweet potatoes, the bursting yellow and red of the maple trees, the tanginess of the Concord grapes, and, finally, the turkey of Thanksgiving, my favorite holiday.Winter in America will always call to mind the brilliant sun and blue sky, with piercing cold and crisp air and the smell of chestnuts in the streets of New York City when I first arrived in 1959.In Connecticut, winter is the smell of burning wood in the fireplace, comforting bean stew and split pea with ham soup, cheese fondue and the feasts of the holidays, which we celebrate with oysters, capon or goose, foie gras and chocolate truffles. This is the best time for small children, and I can see myself and my daughter, Claudine, making caramel candies in the snow.I recall lazy afternoons with a good book by the fireplace, and long walks with my dog along the deserted beach battered by cold wind under a gray and black sky.The greatest taste for me may be a perfect crunchy baguette slathered generously with the very best sweet butter, and the greatest dessert, besides dark, bitter chocolate, may be the succulent apricot or strawberry jams made with very ripe fruits and spread thickly on pieces of warm brioche.My greatest ritual is sitting every night at the dining-room table with my wife and sharing our meal and one, sometimes two, bottles of wine and discussing the events of the day. Throughout the last five decades, this daily ritual has been ingrained so profoundly within us that we could not live without it, and this is how food memories are made.In the words of Voltaire, “Imagine how tiresome it would be to have to eat three times a day if God had not made it a pleasure as well as a necessity.” I hope that you enjoyed traveling with me along my memory lane, and that you will share your table in a daily ritual with your loved ones and enjoy life to the fullest.Happy cooking!© 2015, The New York Times News Service

Advertisement